The Question: What is Resurrection?

The latest in my Christian metaphysics and First Principles series: What does Scripture reveal? What's the difference between resurrection and resuscitation? What is the General Resurrection?

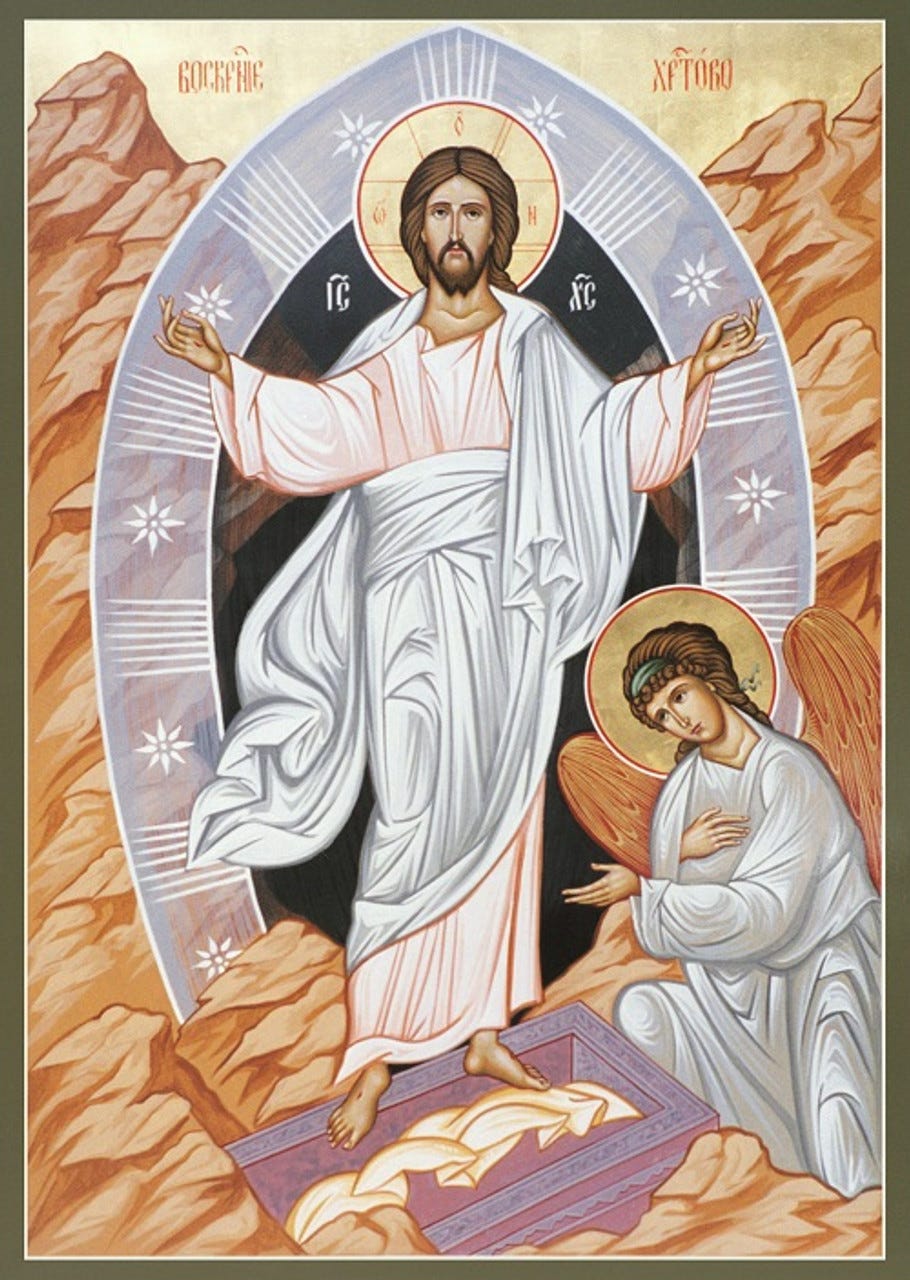

The central teaching of orthodox Christianity is that after having been crucified and having died three days earlier, on the first day of the week, Jesus Christ rose from the dead. Without this, everything else falls apart. C.S. Lewis puts it rather plainly in his marvelous little book, Miracles: “Death and Resurrection are what the story is about; and had we but eyes to see it, this has been hinted on every page, met us, in some disguise, at every turn, and even been muttered in conversations between such minor characters (if they are minor characters) as the vegetables.”1 As the Blessed Apostle put it, if Christ has not been raised, what’s the point?2 Jesus did not merely seem to die, nor was his resurrection the appearance of his spirit. His body was dead for three days, and his body was resurrected, fully alive, on the third day. But this begs the question, just what exactly is resurrection?

The first thing we can say is that resurrection and resuscitation aren’t the same thing. Resuscitation is the restarting of a person’s heart and breathing after both have stopped—usually for a short time (minutes rather than hours). Modern medicine has several tools aimed to accomplish this: CPR, electric shock, administration of epinephrine, naloxone, or other drugs, etc. A person who has been resuscitated is returned (although sometimes with deficiencies due to lack of oxygen) to the life they were living before their breathing and heart stopped. A key Biblical example of this is the resuscitation of Lazarus, narrated in the 11th chapter of the Gospel of John. Scripture doesn’t tell us this precisely, but eventually, somewhere down the line, Lazarus would die a second and final time.

Resurrection, on the other hand, is the inauguration of a new life that is eternal. The Blessed Apostle again: “We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him.”3 While it may resemble resuscitation, resurrection is a permanent condition. Ian McFarland says it well:

The resurrection is not more of this life, but precisely the vindication of this life in its completeness. That is what it means to say with Paul that the life Jesus lives now, he lives to God: that he lives now exclusively by God’s power and not (as was the case with the risen Lazarus, for example) through the revived or continuing power of his human nature (2 Corinthians 13:4).4

We know from Scripture that the resurrected Jesus resembles the Jesus who died because Mary recognizes him in the Garden, and yet, we also can surmise that the pre-resurrected body and the post-resurrected body did have their differences, because it is only after Jesus says Mary’s name that she recognizes him.5 Likewise, the resurrected Jesus possesses human characteristics such as hunger, which we observe when he eats with his disciples after his resurrection.6 But he also possesses super-human characteristics as well, such as walking through locked doors.7 When people ask me if we’ll recognize our loved ones in Heaven, I often remind them of these passages of Scripture. Yes, we’ll recognize them, but neither they nor we will look exactly the same. Our bodies will be perfected—and that doesn’t mean we’ll all be 23-year-old super fit supermodels, either! Perfection in the sense that we will be fully who God has called us to be both individually and communally.

Another dimension of the question, “what is resurrection,” is a bit more theological. In the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the event that serves as the “last straw” before the Jewish leaders conspire with the Roman leaders and say, “Okay, enough’s enough, we’ve got to kill him,” is when Jesus casts the money changers out of the Temple. The sermon writes itself, doesn’t it? Jesus disrupts the economic status quo, and true to form, we are homo economicus, so the government swoops in to put him down once and for all. All of that is right and good and will certainly preach!

But John’s Gospel goes in another direction. John recounts the money changers being cast out very early in Jesus’ ministry—in chapter two of the Gospel, in fact. So what’s the culminating event that causes the religious and political powers that be to decide to kill Jesus? It’s the news that Jesus has raised Lazarus from the dead. Now, as I’ve already pointed out, Lazarus was resuscitated, not resurrected. But John’s Gospel sets forth a theological dimension to resurrection. Here, Jesus is revealed to have power over the one thing that humankind has never conquered: death. That kind of power can topple governments and bring about new religions! In short, if you’re in the government or religious leadership and you see that kind of power coming, you have two choices: either contract with it or kill it.

Resurrection is the scion springing forth against the notion that death will have the last word. It is what transcends all reality, causes tyrants to tremble, and teaches the hopeless to hope once more. Contrary to the French existentialist of the last century, Jean Paul Sartre, life is not meaningless and given over to us to define for ourselves; life without resurrection is meaningless, and apart from the resurrection, what is there left to choose as meaning?

There are, of course, those who attempt to cling to Jesus as a “Great Moral Teacher” and dismiss the supernatural bits. It’s not a new attempt, mind you—all modern heresies have ancient origins at their roots. Even the likes of Thomas Jefferson tried to cling to the Jesus of history while simultaneously cutting away the Christ of faith. The patient never survives such a surgery. C.S. Lewis is reliably plainspoken about this phenomenon in his classic, Mere Christianity:

‘I’m ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don’t accept His claim to be God.’ That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic—on a level with the man who says he is a poached egg—or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God: or else a madman or something worse. You can shut Him up for a fool, you can spit at Him and kill Him as a demon; or you can fall at His feet and call Him Lord and God. But let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about His being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.8

Rowan Williams, in classic style, articulates the theology underpinning Jesus’ passion, death, and resurrection beautifully: “...[T]he cross is not an episode at the end of the life of Jesus but the coming to fulfillment of what that life has been about. This life of utter givenness to God and the other, the neighbor, is already a life that death cannot contain.”9 Then again a few pages later, he adds: “The resurrection displays the integrity, the indestructibility, of the love that has been at work all through. The resurrection is neither an optional extra nor a happy ending, it is the inescapable bursting through of the essential reality of who and what Jesus is.”10

And yet, the effort to divorce Jesus’ life from his resurrection persists. A few weeks ago, my wife and I were visiting one of our favorite bookstores when I stumbled across Elaine Pagels’s new book, Miracles and Wonder: The Historical Mystery of Jesus. If you’ve read my Substack more than once or twice, you won’t be at all surprised to discover that I am no fan of Pagels’s work; in fact, I often point to scholarship like hers as the result of taking the historical-critical method to its most sterile and absurd conclusions: rather than dancing with a living faith and tradition, she and others in her ideological basecamp strangle and slice away at the faith and the tradition until it is nothing more than a dead carapace, then they endlessly fantasize with what could possibly have lived inside that little shell once upon a time, long ago, in a land far, far away.

True to form, her latest book follows the same trajectory: positing theory as fact, conjecture as conviction, and lack of evidence as proof either of absolute existence or of absolute non-existence, whichever best suits her argument at the moment. I promise I’m not writing a book review, so let me come to the point: There is no one in the mainstream of Biblical or historical scholarship that asserts that a person called Jesus Christ did not exist. No one. We have the canonical accounts, we have extra-canonical accounts, we have Roman accounts. All point, not only to his existence, but to him amassing something of a following—though there is variation as to the size of his following. There is not, however, more than a passing acknowledgment of a person named Jesus amassing a following in Roman sources. Likewise, there is no forensic, photographic, or other physical evidence for his existence.

We also have canonical accounts, extra-canonical accounts, and Roman accounts of Jesus having been raised from the dead (though none of the Roman accounts explicitly claim to have witnessed the resurrected Jesus—only that many said he had risen). In the same way as before, there is no forensic, photographic, or other physical evidence for his resurrection. Pagels and like-minded scholars are willing to accept that Jesus existed based on these ancient sources and without the additional forensic, photographic, or physical evidence, but not that Jesus was resurrected based only on these same ancient sources. Allow me to anticipate the rebuttal: Yes, Father Marshall, but people are born all the time! It’s perfectly natural! People don’t ordinarily rise from the dead, however! This line of reasoning seems to boil down to the bizarre idea that we can trust ancient sources and people to describe natural phenomena as we understand “nature” in modern times, but descriptions of supernatural phenomena must be forgeries, cover-ups, or biased superstitions and hypotheses to serve nefarious or well-meaning purposes, depending on one’s perspective. In order for this to be true, one must be absolutely certain not only about one’s own understanding of nature and reality, but also about the nature and reality of a people who lived 2,000 years ago, thousands of miles away.

So let me get this straight: we can trust ancient generations when they describe a world we have come to expect, but we can’t trust them to describe a world that surprises us? I don’t buy it. Of course, there are sharper minds than mine who do buy it, but I’m not in this line of work to be the smartest kid in the class. I’ve been surprised by the world around me (and by the manifold ways God continues to act in my life) to know that if you don’t at least occasionally find yourself utterly baffled by this big blue marble and the people and other natural things that call it home, you’re not paying attention.

Pastorally, I find myself saying to folks, “Would you trust a cardiology who didn’t believe in medicine? How about an attorney who didn’t believe in the Rule of Law? An accountant who didn’t believe in GAAP (generally accepted accounting procedures)? Then why would you rely on a scholar of a religion they don’t believe in to inform and guide your faith?” Let me say the quiet part out loud: for folks ideologically aligned with Pagels, it’s not that “the resurrection might or might not be true, if only we had concrete evidence in one direction or another,” it’s actually, “the resurrection can’t be true because it doesn’t conform to our understanding of nature, and no amount of evidence will change my mind.”

At the end of the day, religion (all religion) is an effort to organize reality around a shared experience of power. In the grand scheme of efforts to organize reality around some or other power, there are a few hopeful organizing possibilities, and more monstrous organizing possibilities than one could possibly count. I’m sticking with the power that brings resurrected life out of death and, even at this very moment, is sustaining and redeeming us.

What do you think? Leave a comment! Share the article!

C.S. Lewis, Miracles in The C.S. Lewis Signature Classics (HarperOne, 2017), 388.

1 Corinthians 15:14, paraphrase.

Romans 6:9, NRSV.

Ian A. McFarland, The Word Made Flesh: A Theology of Incarnation (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2019), 165.

John 20:11-18, NRSV.

Luke 24:36-43.

John 20:19-20.

C.S. Lewis Mere Christianity in The C.S. Lewis Signature Classics (HarperOne, 2017), 50-51.

Rowan Williams, The Sign and the Sacrifice: The Meaning of the Cross and Resurrection (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2017), 45.

Williams, 45-46.

You . have a great gift to explain something so deep in such a short clear article. Looking forward to more of your writings.